As Native American Heritage month approaches, First Things First recognizes that the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has declared 2022 to 2032 as the International Decade of Indigenous Languages. This designation is working toward building a global community for preservation, revitalization and support of indigenous languages worldwide.

This is an important early childhood issue, since research shows that the best possible time to learn a second language is during early childhood. According to researchers from the University of Washington, at birth, a baby brain can tell the difference between all 800 sounds that make up all the world’s languages. Each language uses about 40 of those sounds.

Some First Things First regions support a Native Language Preservation Strategy to give parents and other caregivers tools to promote their children’s language development that are appropriate to their children’s age and culture.

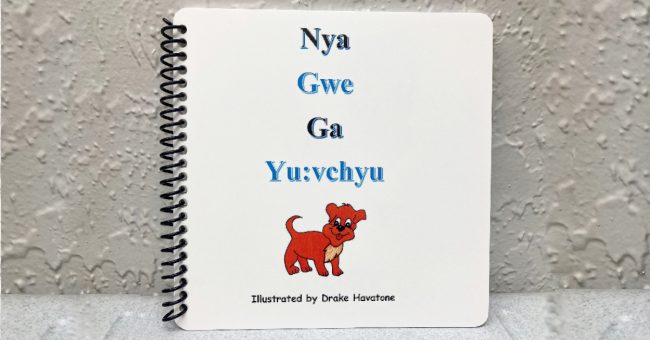

For example, in the FTF Hualapai Tribe Region, a recent children’s book in the Hualapai language is designed to support families’ efforts to begin teaching the language at an early age as a way to strengthen culture and identity.

Over the past few years, community leaders have encouraged a child’s first language to be Hualapai.

“Regional council members wanted to support the language building efforts,” said FTF Hualapai Tribe Regional Director Tara Gene. “We started with one book on one topic and will go from there.”

The native language project between the Hualapai Tribe’s Cultural Resources Department and FTF started about a decade ago when the FTF Hualapai Tribe Regional Council funded the creation of a set of bilingual storybooks in English and Hualapai for families of babies, toddlers and preschoolers.

This time, the book is based on sight words with names of animals, colors and numbers, all in the Hualapai language. A local artist with the cultural center created the art for the first book.

More and more families are interested in raising their children bilingually – for many reasons including the positive research that a second language aids brain development, supporting cultural connections and expanding future professional opportunities.

Beatrice Lee is the director of the Language Preservation Department for the San Carlos Apache Tribe. Her department works with almost 50 early childhood teachers to teach the teachers the Apache language and show them how to teach it to young children.

First Things First provides funding for teachers to read and distribute storybooks to the early childhood classrooms, Lee said.

Bernadette Talkakai, who works for the Language Preservation Department, visits the early learning classrooms where she models lessons for the teachers that range from circle time, finger play and singing, while she focuses on the Apache language.

“I incorporate myself into the classroom, mainly focusing on the language,” Talkakai said. “For example, I’ll tell the children, ‘come sit down’ using the language.”

She’s created classroom materials, such as posters and translated classic books, like Eric Carle’s “Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What do you See?” into Apache for the teachers. Many times she’ll translate basic words for the classrooms’ word walls.

An additional challenge comes with working with teachers who themselves are learning the language.

“Yes the teachers aren’t fluent, but they have the knowledge to know the basics,” said Talkakai, who was an early childhood teacher for many years. “In a preschool classroom, a lot has to do with schedules and transitions. ‘Let’s go wash our hands.’ It’s the routine schedule that they’re on every day. That’s the type of basic language that they use in the classroom.”

The work being done is important because the Apache language is endangered, Talkakai said. Up until 10 years ago, Apache wasn’t written. It was strictly an oral language.

“For us to keep it, we’re going to have to preserve it,” she said.

A language survey from recent years found that a lot of households of the younger generations don’t speak Apache, Lee said. “It was about 80% of our young families. Our goal is to get more teachers to keep language alive by teaching our younger generation coming in. That’s what we tell the parents, grandparents, language should be spoken at home no matter what.”

Recently, the Ak-Chin Indian Community linked their early childhood program with their language program to provide an immersion classroom. It was a goal that’s been a few years in the works, said Bianca Schrader, the early childhood education program manager for the Ak-Chin Indian Community.

There are about 49 children in the program, which provides bilingual instruction in the O’odham language and English.

“All of my staff know at least preschool-level O’odham. We’re still using it making sure the kids know the simple commands,” Schrader said. “Currently we have two fluent speakers on staff and others who can understand and speak the language. It’s exciting and a big job to get everybody on board.”

Teaching language has to be a community effort, Schrader said.

“We have to create those partnerships within the community by presenting it to them and showing them what we do in the classroom,” she said.

“Those children are going to grow up. The youth workers that work with us now, they were our preschoolers from 10 years ago. It’s important for everyone to understand that your language is your culture. Not a lot of people have a language, it’s what sets us apart from other communities. We want them to get excited about it, but it’s going to take a community effort.”

The next step is to call on families, especially elders who speak the language, to teach the language to others, including young children and their parents.

“We don’t want the language to die within this community,” Schrader said. “It’s really important for this community to understand that if they don’t speak the language, it’s going to go away. People don’t know the severity of that.”